The “New” Tasmanian Energy Business Model – Who Really Pays?

When the Federal Government set its course towards a renewable future, it opened the door for big-ticket projects like Marinus Link and Battery of the Nation. For Tasmania, the promise has always been that we can leverage our hydro resources and position ourselves as the nation’s “renewable powerhouse.” But look beneath the surface and the new energy business model emerging for Tasmania is far more complicated—and far less rosy for consumers.

At its heart, the model is driven by federal climate and energy policy, implemented through the Australian Energy Market Operator’s (AEMO) Integrated System Plan (ISP). This provides the rationale for greater interconnection between states, with Marinus as Tasmania’s piece of the puzzle. But once we trace the flow of impacts through transmission charges, wholesale energy price shifts, and subsidies, a picture emerges of households and businesses footing the bill, while Hydro Tasmania (HT) is asked to play banker to the whole arrangement.

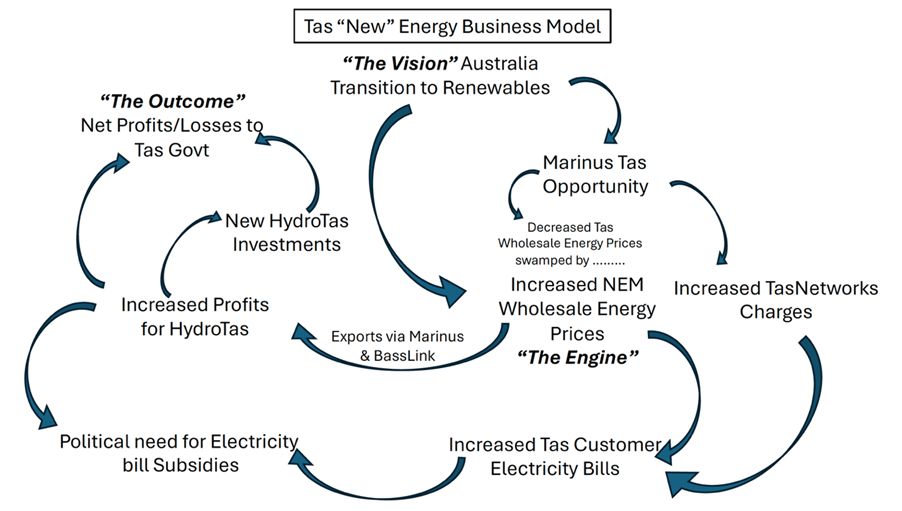

The New Business Model in a diagram looks something like this:

- Federal renewables policy creates opportunities for interconnection projects.

- Marinus Link increases TasNetworks’ transmission charges—costs ultimately passed through to Tasmanian customers.

- Those charges are partially offset by a local reduction in wholesale electricity prices from Marinus.

- But here’s the catch: The Deloitte Market Modelling report commissioned by Tasmanian Treasury predicts overall wholesale prices in both Victoria and Tasmania will rise sharply as coal exits and reliance on gas grows. That upward trend swamps any local benefits certainly in the short to medium term.

- The result: significantly higher electricity bills for every customer—residential, business, and major industrials.

- Meanwhile, Hydro Tasmania profits rise, thanks to higher national wholesale prices and expanded export opportunities via Basslink and Marinus.

- Those profits, however, won’t simply translate into a dividend bonanza for the state. From what we are told, the additional profits will be required to:

- Subsidise Tasmanian customers to soften the blow of higher bills.

- Fund new generation capacity to fill Marinus’ export “pipeline.”

- Net outcome: the “rivers of gold” promised for Hydro are diluted, while Tasmanian households, business and major industrial customers remain exposed to price shocks.

Treasury’s commissioned Deloitte report puts some numbers around this shift. Under the “No Marinus” scenario, Tasmania’s wholesale prices would rise moderately—from around $50/MWh towards $60/MWh—because our exposure to mainland market volatility is limited with only Basslink.

With Marinus Stage 1, however, Tasmania becomes more tightly bound to Victoria’s market. Prices converge. In Victoria, wholesale prices may fall by a mere $4–$11/MWh (not exactly transformative, given forecasts of around $140/MWh). For Tasmania, the impact is much more severe: wholesale prices rise by about $40/MWh – an increase of 59% relative to the “No Marinus” case.

In other words: Tasmanian households and businesses pay significantly more for their wholesale energy, while Victoria gets a modest discount compared to the No Marinus case.

The sceptic in me suggests that this is a business model built on contradictions. It asks Tasmanians to believe that higher bills for them are somehow in their long-term interest. It assumes that Hydro’s increased profits will seamlessly flow into subsidies, even as Hydro shoulders new investment risks. It imagines that “integration” with the mainland market will deliver stability, when in fact it amplifies our exposure to national volatility.

Hydro Tasmania, for its part, will be expected to support Marinus with new generation – whether owned directly or via purchase agreements. That means more capital investment, more borrowing, and more pressure on profits. In the short to medium term, this means smaller dividends to the state, not bigger.

And so, the net result for Tasmanians is not “cheap, clean energy for all” but a delicate juggling act: higher bills upfront, hidden subsidies downstream, and uncertain returns in the long run.

We’ve been here before. There are also lessons to be learnt from Basslink. Two decades ago, Basslink was justified on the promise of surplus hydro and new gas generation creating export opportunities. Instead, inflows dropped, gas proved too expensive, and consumption never reached the rosy forecasts. Basslink became a cautionary tale, not a triumph.

Today, the same risks loom. Overestimated demand, overstated benefits, and understated costs. Except this time, the stakes are higher—because Marinus and Battery of the Nation together rewire Tasmania’s entire energy business model.

On top of this, there’s something else occurring which may have dramatic effects – Hydro Tasmania’s annual inflows and what has been assumed. The current system is valued as a 8,900 GWh system which is the amount of electricity which can be generated from average inflows. But the two most recent years 23/24 and 24/25 have seen inflows fall below 7,000 GWh which has dragged the ten year average down to 8,500 GWh . This should mean that future projections may need to be adjusted if they are to be based on prudent assumptions. Furthermore, it means the value of Hydro’s assets will need to be revised downward which in turn effects the amount of debt it can service. There are far reaching ramifications if future inflows are less than historic averages which is highly likely to be the case.

For all the talk, the central question remains: will this new model genuinely serve Tasmanians, or will it lock them into higher bills while HT props up the system through subsidies?

Energy transitions are never painless, but the least Tasmanians deserve is honesty. The “New Tas Energy Business Model” is very unlikely to be about rivers of gold flowing to the state budget. It’s about managing rising national wholesale prices, masking local bill shocks with subsidies, and hoping that Hydro’s role as both generator and guarantor won’t leave Tasmanians worse off.