Over the next three weeks, I will be posting a new post daily, or thereabouts, related to how Hydro Tasmania actually earns money, how the National Electricity Market shapes its fortunes, and why the numbers in its accounts now matter more than at any time in the past two decades. It also seeks to dismantle the myths that have dominated public debate.

This second post is Chapter 2 – Electricity and the NEM – The Basics Tasmania Was Never Told. There are 18 Chapters in total. I thank John Lawrence for his assistance in preparing this information, his attention to detail and research over many years as we have worked together to better understand one of the most complex areas that impact our state, economically and functionally.

Glossary of acronyms used in this chapter

AEMO – Australian Energy Market Operator: Runs the NEM, dispatches generators, manages system security, and publishes key planning documents.

FCAS – Frequency Control Ancillary Services: Markets that pay generators or batteries to help stabilise system frequency.

IRR / IRRs – Inter‑Regional Revenues / Inter‑Regional Residues: The financial mechanism that captures price differences between NEM regions. Historically a major windfall for Hydro.

LGC – Large‑scale Generation Certificate: A renewable energy certificate created for each MWh of eligible renewable generation.

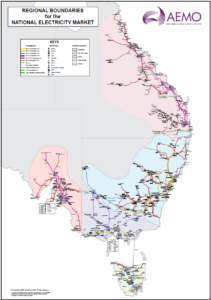

NEM – National Electricity Market: A collection of five separate regional markets linked by interconnectors.

PPA – Power Purchase Agreement: A contract to buy or sell electricity at an agreed price.

RRP – Regional Reference Price: The official price for each NEM region. Tasmanians pay the Tasmanian RRP.

Chapter 2: Electricity and the NEM – The Basics Tasmania Was Never Told

Before we can talk about Hydro’s finances, Basslink’s windfalls, Marinus’s promises, or the $65 million in PPA losses quietly buried in Hydro’s accounts, we need to strip electricity back to first principles. Not the physics – the economics. Because almost every misunderstanding in Tasmanian energy policy comes from treating electricity like a normal commodity. It isn’t. And the National Electricity Market (NEM) certainly isn’t a normal market.

Tasmania is part of the NEM, but the NEM is not a single market with a single price. It is a network of five separate regional markets, each with its own Regional Reference Price (RRP). Tasmanians pay the Tasmanian RRP – not the Victorian price, not a blend, not a weighted average. This one fact underpins everything that follows.

Victorian prices do not flow across interconnectors. Not now, not after Basslink becomes regulated, and not when Marinus is built. Interconnectors move electricity, not settlement prices.

And here is the key point: Victorian prices do not flow across interconnectors. Not now, not after Basslink became regulated, and not when Marinus is built. Interconnectors move electricity, not settlement prices. For electricity to flow between regions, there must be a price difference. That is the condition that activates a flow. When Tasmania imports, the Tasmanian price must be higher than Victoria’s. When Tasmania exports, the Tasmanian price must be lower. This has always been true, under every regulatory model.

But – and this is crucial – a flow tells you nothing about who benefits. The dispatch engine moves energy because prices differ, not to give Tasmania access to Victorian prices. Negative Victorian prices never reach Tasmania – the system isn’t built that way. Negative prices would only appear here if the Tasmanian RRP itself went negative, which for Hydro would be catastrophic.

Once these basics are clear, the rest of the story – the Inter-Regional Revenues (IRR) windfalls, the Large Generation Certificates (LGCs) losses, the myths about “cheap Victorian imports”, the circular logic of Marinus – becomes impossible to spin.

Electricity is unlike anything else we trade. Until very recently, it couldn’t be stored in the grid. It had to be produced at the exact moment it is to be consumed. When demand rose, generation had to rise instantly. When demand fell, generation had to fall just as quickly. An unbalanced system was an unstable system. This could lead to serious risk to the electricity system and failures resulting in power outages. This is why hydro has always been so valuable: it can respond in seconds. And it is why droughts matter. When storages fall, Tasmania loses its most flexible, reliable tool.

Prices in the NEM are not set by negotiation or bilateral deals. Every five minutes, the Australian Energy Market Operator) AEMO stacks generator bids from cheapest to most expensive and dispatches them until demand is met. The price paid to all generators is the price of the last – the most expensive – generator dispatched. Economists call this marginal cost pricing. Understand marginal cost pricing and you are halfway to understanding the NEM.

It explains why cheap generators can earn high prices. It explains why expensive mainland generators can drag Tasmanian prices up. It explains why “cheap Victorian power” is not a guaranteed benefit. And it explains why “high Victorian prices” do not automatically deliver Tasmanian windfalls.

There is no haggling. No “Tasmania buys from Victoria” or “Tasmania sells to Victoria”. Just dispatch and price.

Interconnectors like Basslink, and later Marinus, do not merge regions into a single market. They simply allow electricity to flow between them when it is both economically favourable and physically possible. When the link is unconstrained, prices tend to converge. When it is constrained, prices diverge. And constraints matter far more often than the public debate acknowledges.

This is the part almost no one in Tasmania understands. Interconnectors have technical limits – thermal, voltage, stability, system strength – that determine how much power can safely flow at any moment. When these limits impact electricity flow, they override price signals. Tasmania can be forced to import even when Victorian prices are high. It can be blocked from exporting even when Victorian prices are higher. The direction of flow is not a policy choice. It is the outcome of physics and constraints.

This single fact destroys the simplistic claims that Tasmania “benefits from cheap imports” or “profits from high export prices”. Sometimes it does. Often it doesn’t. And the public is rarely told which is which.

Batteries have added a new layer to this story and one that has barely entered Tasmanian public consciousness. For most of the NEM’s history, hydro was the dominant flexible resource. It could ramp quickly, shift energy into the evening peak, and provide Frequency Control Ancillary Services (FCAS) when the mainland was short. Batteries have changed all of that.

They flatten prices by charging during low‑price solar hours and discharging into the evening peak. They shorten and soften the peak. They compress the spread Hydro once relied on. They dominate FCAS because they respond in milliseconds, set prices, reduce or even eliminate scarcity events, and erode Hydro’s traditional advantage. And they reshape Basslink and Marinus flows by soaking up excess solar, discharging into the peak, reducing the need for Tasmanian imports, reducing the value of Tasmanian exports, and compressing the arbitrage that once drove IRR windfalls.

Hydro still matters but it is no longer unique.

The NEM is a mainland‑centric market. Tasmania is a small, hydro‑dominated region bolted onto the edge of this system. Our interests are not the same as Victoria’s or NSW’s.

And all of this is happening inside a system that was never designed for Tasmania’s interests. The NEM is a mainland‑centric market built for coal retirement, large‑scale solar and wind, massive transmission builds, and mainland reliability challenges. Tasmania is a small, hydro‑dominated region bolted onto the edge of this system. Our interests are not the same as Victoria’s or NSW’s. Yet our public debate often assumes they are.

Why does this matter? Because if you misunderstand these basics, you misunderstand everything that follows: Why Hydro earned over $100 million in IRRs in 2024/25. Why those windfalls disappear under APA current and future operation of the link. Why PPAs lost $65 million in 2024/25. Why Marinus raises Tasmanian prices. Why new generators depend on PPAs. Why PPAs depend on Marinus. Why the whole system has become circular. And why Hydro’s financial health is inseparable from the State’s fiscal health.

Tasmania is being asked to make multi‑billion‑dollar decisions on the basis of slogans, redacted documents, and misunderstandings about how electricity and the NEM actually work.

This series exists to fix that.

Next, in Chapter 3, we turn to the heart of the Tasmanian system: Hydro Tasmania – what it is, what it does, and why it matters more than ever.