This post begins a series related to the financial position of Hydro Tasmania with a focus in this post on its underlying profit. This series of 18 chapters outlines how Hydro Tasmania actually earns money, how the National Electricity Market shapes its fortunes, and why the numbers in its accounts now matter more than at any time in the past two decades. It also seeks to dismantle the myths that have dominated public debate. This and the next three chapters (11-13) are critical to understand the importance of Hydro Tasmania, to and for, the State.

I thank John Lawrence for his assistance in preparing this information, his attention to detail and research over many years as we have worked together to better understand one of the most complex areas that impact our state, economically and functionally.

Glossary of acronyms used in this chapter

AETV Aurora Energy (Tamar Valley) Pty Ltd: also referred to as the Tamar Valley Power Station (TVPS), the company is now owned by Hydro Tasmania and operates the closed cycle gas fired electricity facility in the Tamar Valley.

FCAS – Frequency Control Ancillary Services: Markets that pay generators or batteries to help stabilise system frequency.

GWh – Gigawatt‑hour: A measure of energy. One GWh equals one million kilowatt‑hours.

LGC – Large‑scale Generation Certificate: A renewable energy certificate created for each MWh of eligible renewable generation.

MW – Megawatt: A measure of power (capacity). One MW equals one million watts.

WWF – Woolnorth Wind Farms: Built by Hydro but now owned 75 per cent by Shenhua Clean Energy and 25 per cent by Hydro. Operates wind farms at Bluff Point, Studland Bay and Musselroe – a total of 308MW of installed capacity.

Hydro Tasmania’s Underlying Profit – What It Is, What It Isn’t, and Why It Matters

Hydro Tasmania publishes many numbers each year, but only one of them tells you how the business actually performed in the real world: its underlying profit. This is the figure that strips away the noise – the revaluations, the fair value movements, the accounting adjustments – and reveals the true operating margin of the business that keeps Tasmania’s lights on. It is also the number that matters most for the State Budget, because it determines the dividends and tax equivalents that flow back to government.

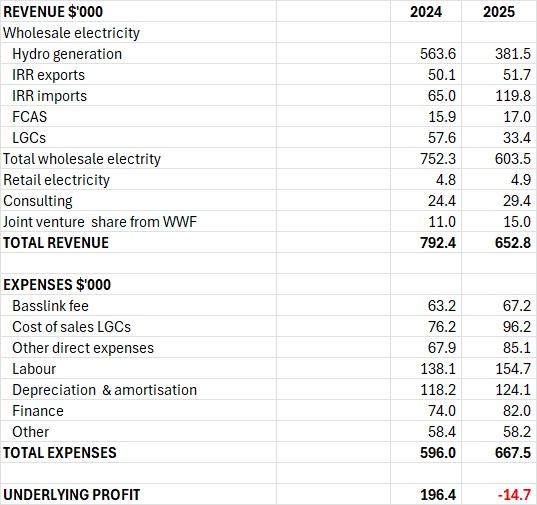

In 2024/25, that number fell from a healthy $196 million to a loss of $14.7 million. Nothing else in the accounts comes close to capturing the scale of the deterioration. Even knowledgeable insiders can’t make much sense of the profit & loss statement because there are two large amorphous amounts, wholesale electricity (in revenue) and direct expenses (in expenses), which need to be unbundled before any meaningful conclusions can be drawn. Which is what we have been trying to do in the nine chapters so far.

Had Hydro adopted accounting standard AASB 18 Presentation and Disclosure in Financial Statements we would have discovered the truth much earlier, but Hydro has delayed adoption of that standard until 2027/28, the last possible date. The Minister could have asked for early adoption, but he appears more wedded to opacity than Hydro.

So let’s have a look at Hydro’s P&L with the break-ups we have manage to estimate. The story becomes a lot clearer.

The reconstructed profit and loss statement for the 2 years relates only to the parent company Hydro Tasmania but this is where all the action is. It excludes subsidiary companies Momentum Energy, an electricity retailer, and Aurora Energy (Tamar Valley) Pty Ltd (AETV) or Tamar Valley Power Station (TVPS), the company which owns and operates the closed cycle gas fired electricity facility in the Tamar Valley. Almost all assets, borrowings and risks are with the parent company. All future reference in this series will refer to numbers in the parent company unless otherwise indicated. All the figures are from Hydro’s financial reports except for the break-up of wholesale electricity where the Inter-Regional Revenue (IRRevenue), Frequency Control Ancillary Services (FCAS) and Large Generation Certificates (LGC) are best guesstimates based on various pieces of public information because Hydro refused to confirm because of supposed commercial in confidence concerns.

The figure for hydro generation is the residual amount remaining after the IRRevenue, FCAS and LGC amounts are deducted from wholesale electricity. Direct expenses have been unbundled – the Basslink fee we noted in Chapter 5 and the LGC cost of sales as noted in Chapter 6 have been separated out.

The additional breakup provides a better basis for understanding Hydro’s business. It may not be 100% accurate but it’s the best estimate based on available information.

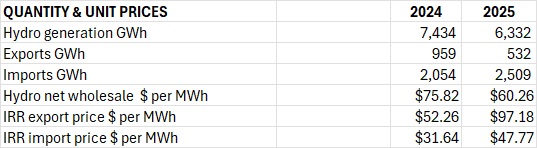

The following table gives a snapshot of the quantity estimates and the calculated unit prices.

Once the table of revenue and expenses is presented the structure of Hydro’s underlying profit becomes unmistakable. The top half of the table shows where Hydro’s money actually comes from: the electricity it generates, the IRRevenues it earns when power flows across Basslink, the LGCs it sells, the FCAS services it provides, and the smaller contributions from consulting, some minor retail operations details of which are yet to be disclosed, and its joint venture interest.

In 2023/24, these combined to produce just over $792 million in revenue. A year later, that figure had fallen to $653 million – a drop of almost $140 million.

The fall is not evenly spread. Generation revenue alone fell by more than $180 million, from $563.6 million to $381.5 million, reflecting the simple reality that Hydro had less water and fewer opportunities to generate. Hydro generation fell by 1,202 GWh to an historic low of 6,332 GWh. Not only that but prices crashed also, to $60 per MWh. This is the average wholesale price achieved by Hydro for the year. IRRevenue, by contrast, rose sharply – imports and exports together delivered $171 million in 2024/25, compared with $115 million the year before. These figures are based on public figures for gross IRRevenues less an estimate for transmission losses. The increase in IRRevenues cushioned the blow but could not offset the collapse in generation revenue or the structural losses emerging in LGCs, where revenue fell from $57.6 million to $33.4 million as certificate prices halved.

Below the revenue line, the table shows the other half of the story: the cost of running the system. The Basslink fee was reasonably steady ($67 million in 2024/25), but it was the LGC cost of sales including the inventory write down, which rose to $96 million compounding the drop of LGC sales. Labour costs increased by more than $16 million. Depreciation and amortisation rose modestly. Finance costs climbed from $74 million to $82 million as debt increased. None of these movements is surprising on its own, but together they pushed total expenses from $596 million to $668 million.

When you place the revenue and expense for the two years side by side, the deterioration in underlying profit becomes unavoidable. In 2023/24, Hydro earned $792 million and spent $596 million, leaving an operating surplus of $196 million. In 2024/25, it earned $653 million and spent $668 million, producing an operating loss of $14.7 million. The swing – more than $210 million – is not the product of accounting adjustments or revaluations. It is the direct result of the numbers in the table: less generation, lower derived prices, weaker LGC revenue, higher LGC costs, and rising operating expenses.

The table also makes clear what did not cause the collapse. Export revenue held steady despite lower volumes, thanks to a couple of high‑priced weeks. Imports did not depress wholesale revenue; they increased IRRs. The problem was not mismanagement or a single bad decision. It was the combined effect of drought, market conditions, and structural shifts in Hydro’s operating environment – all of which show up cleanly in the revenue and expense lines.

When the numbers are read in this way – not as isolated line items, but as a coherent operating story – the collapse in underlying profit becomes unavoidable. It is not the result of a single bad decision or a momentary lapse. It is the arithmetic consequence of less water, lower derived prices, structural LGC losses, higher settlement costs, and rising operating expenses. The IRR windfall softened the blow, but even a record $171 million could not reverse the underlying deterioration.

This is why underlying profit matters. It is the only number that reflects Hydro’s real trading performance. It tells us whether Hydro is generating enough cash to pay dividends, service debt, maintain its assets, and support the State Budget. And in 2024/25, that number was negative.

But it’s the loss of IRRs and the continuing losses from LGCs which are going to be difficult for Hydro to counter.

The next chapter turns to the balance sheet – the other half of the story – where the revaluations, liabilities, debt, and structural pressures sit. If underlying profit shows how Hydro performed this year, the balance sheet shows how much risk it is carrying into the next year.